Sip or Guzzle: How Frequently Should You be Fuelling?

You will likely have encountered numerous recommendations for the amount of carbohydrate you should be exercising each hour during exercise. As I outlined in the article on substrate utilisation, the amount of carbohydrate you will be utilising, and thus requiring replenishment, depends on the duration and intensity of the exercise

What is less commonly addressed though is how this intake should be dosed. For example, if the recommendation is to feed with 60g/hr of carbohydrate, should you be guzzling the full 60g of carbs in one go on the hour every hour, or are you better off sipping on smaller doses at more frequent intervals?

Well, I have taken a big swig of the relevant evidence on and will dose my findings over the following paragraphs to help you better digest this topic.

Gastric Emptying

One may presume that consuming larger doses of carbohydrates in one go could overload the intestinal system and increase the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) issues. Following a similar logic would have us believe that in contrast, consuming smaller and more frequent doses would help digestion by allowing the gut to continuously process the carbohydrates without becoming overwhelmed.

Gastric emptying is the term for the process by which the contents of the stomach are moved into the small intestine for further digestion and absorption. However, there isn’t a linear relationship between the quantity of matter in the stomach and gastric emptying. As fluid enters the stomach, this additional content applies an increased pressure and stimulates stretch receptors, therefore increasing the rate of gastric emptying (Mears et al., 2020).

Carbohydrate oxidation following exogenous intake has been researched extensively, with typical protocols involving an initial larger ingestion of a carbohydrate-containing beverage in a dose of 400-600ml immediately before exercise followed by doses of 100-200ml at 10-15 minute intervals during exercise. Although this has been tolerated well in laboratory-based experiments, such strategies are not always feasible in the real world due to practical considerations and the risk of GI issues. A large volume may be more difficult to ingest in one go, but frequent consumption of smaller volumes may also be inconvenient when exercising at higher intensities or access to the fuel source is difficult (e.g. technical sections). Therefore, there remains a question surrounding the balance between volume and frequency to maximise carbohydrate delivery and utilisation, while minimising GI disturbances (Mears et al., 2020).

Digesting the Evidence

There are a few studies which give clues as to what could be the optimal strategy.

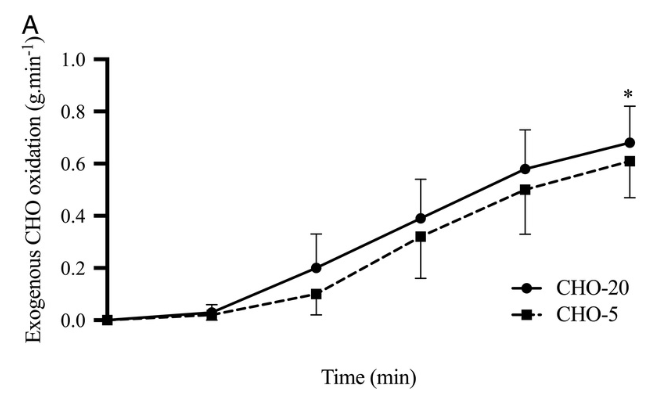

The most frequently cited study is that conducted by Mears et al. in 2020 who investigated how sports drink intake patterns affected exogenous carbohydrate oxidation among 12 well-trained male runners. The participants were subjected to three trials where they ran for 100 minutes at 70% of VO2 max. One consumed water as a control, and two employed drinking strategies using the same total volume of 1 litre of sports drink with 100g glucose. This was either consumed as 200ml doses every 20 minutes (CHO-20) or 50ml doses every 5 minutes (CHO-5).

Their results showed that exogenous carbohydrate oxidation during exercise was 23% higher in CHO-20 than in CHO-5. There were no differences between the other measured factors such as blood sugar, fat burning or total energy expenditure. Importantly, gastric comfort was not affected, with a similar level of discomfort recorded for both trials.

Larger, less frequent doses therefore allowed for better utilisation of the drink. The authors put this down to the larger quantities provided in CHO-20 likely increasing gastric pressure, resulting in increased gastric emptying and thus absorption. The small intakes may have instead remained in the stomach longer and delayed absorption.

Mears et al. (2020). Exogenous carbohydrate oxidation rates during exercise in CHO-20 and CHO-5.

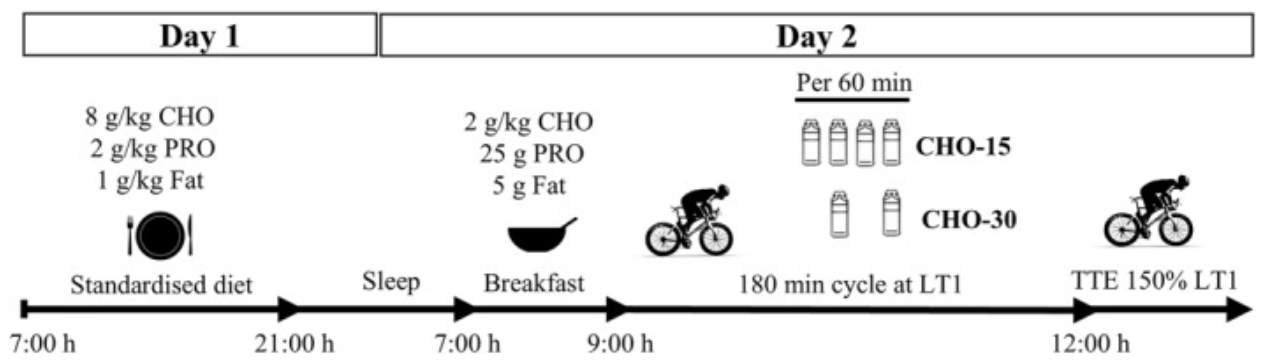

The Mears et al. (2020) study was performed on runners, which could be seen as a limitation to its applicability to cycling. Jones et al. (2025) identified this gap in the research market and set out to investigate the effects of different carbohydrate ingestion patterns on physiological responses to exercise, substrate oxidation, GI symptoms and exercise capacity. However, they did not investigate specific exogenous carbohydrate oxidation so could not explicitly distinguish between utilisation of internal and ingested carbohydrate sources.

Their study involved subjecting 20 recreationally active males to a 180 minute cycling test at LT1 (Aerobic Threshold) where they consumed 90g/hr of carbohydrate gels, either as 22.5g every 15 minutes (CHO-15) or 45g every 30 minutes (CHO-30). Their results demonstrated no significant difference in any of the physiological responses, except for blood glucose which saw a greater increase in CHO-15 during the first 30 minutes of the trial. As with the Mears et al. (2020) study, there was no significant GI distress reported.

Jones et al. (2025) conclude by suggesting that the use of a larger carbohydrate dose at less frequent intervals in endurance cycling is a feasible and perhaps more practical nutritional strategy, with no meaningful negative impact on physiological responses to exercise, whole‐body substrate oxidation or GI discomfort compared to more frequent feeding frequencies.

Jones et al. (2025). Schematic of study protocol for each condition, where participants followed a standardised high CHO diet for 24 h prior to completing a 180 min steady state cycling protocol followed by an exercise capacity test.

How Much is Too Much?

So, if both of the previously cited studies suggest that more quantity at less frequent internals is often better (or, at least not detrimental), then where is the limit?

A clue may lie in research carried out by Stocks et al. (2016) on the effects of carbohydrate dose and frequency on metabolism, GI discomfort, and cross-country skiing performance. Their protocol involved 10 men and 3 women completing four 30km roller skiing time trials on a treadmill whilst consuming a carbohydrate solution. This was provided at either high doses of 2.4g/min (HC) or moderate doses of 1.2g/min (MC) and each at either high frequencies (HF) of six feeds or low frequencies of two feeds (LF).

Although there was no significant difference in performance time between the different trials, GI discomfort was higher in HC-LF compared with all other trials. The single feed volumes in the LF trials was significantly higher at an average of 686ml per feed, but total ingested fluid volumes were not significantly different between the trials. The authors attribute this observed GI distress to limitations in the rate of carbohydrate absorption from the gut, meaning that a large proportion of the carbohydrate ingested in a single feed would remain in the gut for an extended period of time.

There is likely to be a balance between adding sufficient quantity to the stomach to trigger gastric emptying and not pushing it too far as to bring about GI distress. Where this tipping point lies hasn’t quite been identified by the limited research carried out on this subject, and is more than likely to involve an individual element. Nevertheless, pointers may lie in a study from 1974 where Costill & Saltin examined progressively larger volumes of fluid ingestion and found increased gastric emptying up to 600ml.

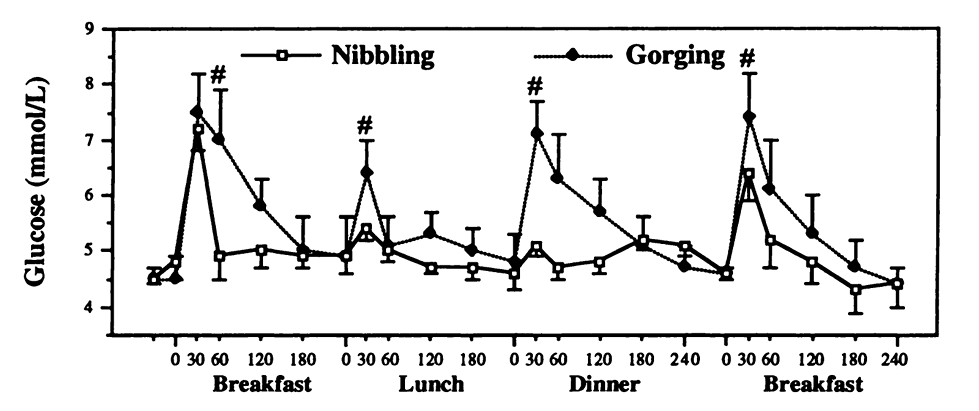

Another downside of the too much in one go approach may be its impact on blood glucose levels, potentially leading to spikes and crashes which are often synonymous with inconsistent energy availability and increased GI distress. Burke et al. (1996) looked at the effect of the frequency of carbohydrate feedings in a post-exercise context by comparing intake of large carbohydrate meals (“gorging”) with a pattern of frequent, small, carbohydrate snacks (“nibbling”). The gorging diet (four large meals) produced large increases in blood glucose and insulin concentrations after each meal, which returned to baseline values within 60-90 minutes. Conversely, the nibbling diet (hourly snacks) produced a flatter profile for blood glucose and insulin concentrations.

Spikes in blood glucose can result in oxidative stress and inflammation even in people without diabetes and are also reported to have effects on mental health, energy, mood and sleep (Avner & Robbins, 2025). All factors that can be detrimental when exercising, and even more so in multi-day ultra-distance events.

Burke et al. (1996). Blood glucose profiles over 24 h with a gorging or a nibbling diet in eight well-trained subjects after glycogen-depleting exercise.

What About ‘Real’ Foods?

One major limitation of the research on this subject is that they all focus on carbohydrate intake via fluid sources. In practice, ultra-distance athletes will be consuming their fuel in a large part via solid, or ‘real’, foods, whether during events or whilst training. One could therefore question how ingesting carbohydrate in solid forms affects gastric emptying and oxidation rates.

An example of a study that directly compared whether carbohydrate in solid form is as effectively oxidised as carbohydrate in a liquid solution comes from Pfeiffer et al. (2010). Whilst riding for three hours, a group of well-trained cyclists received either a carbohydrate drink or an energy bar plus water (to match the amount of fluid ingested for each). There was also a control trial where the participants only consumed water. The energy bar contained the same amount of carbohydrate as the drink and was low in protein, fat and fibre. Overall exogenous carbohydrate oxidation rates were not significantly different between the two groups, suggesting that the form in which carbohydrate is ingested does not really matter for the oxidation of the carbohydrate.

This doesn’t quite answer whether the energy bar would have produced the same outcome without fluid intake being matched but can serve as an additional reminder as to the importance of adequate hydration.

Sip or Guzzle?

Even through the evidence gathered through research studies conducted in a laboratory setting, I can’t draw a definitive conclusion for there being an optimal way to be dosing carbohydrate intake. A minimum amount of quantity is required within the stomach to increase gastric pressure and thus trigger gastric emptying so being too meagre with your sipping or nibbling may not be enough for your body to start making use of that consumed energy immediately. However, this could feasibly be offset by starting exercise with a reasonable quantity of fluid in the stomach which could equally be water as any carbohydrate solution, if carbohydrate ingestion is to follow.

The upper limit of absorption and oxidation appears to be linked to the maximal rates of gastric emptying and associated symptoms of GI issues. In the words of Asker Jeukendreup:

“The optimal amount of ingested carbohydrate should ideally be the amount that results in the maximal rate of exogenous carbohydrate oxidation without causing gastrointestinal discomfort.”

There are also practical considerations here. Feeding at precise periods is not always feasible such as when descending or having to keep both hands firmly gripped on the handlebars during technical sections. Having a strategy of feeding at 20-30 minute intervals should be a starting point and then adapted as circumstances develop. What does seem quite clear though is that taking on too much in one go is far from optimal, both for its potential impact on blood glucose levels, slowing gastric emptying and causing GI distress. Provided that there is adequate associate fluid intake, the source of the carbohydrate can equally be solid. However, it must be noted that foods higher in fat, protein and/or fibre are likely to slow gastric emptying and thus reduce energy delivery.

As with many things, everything in moderation appears to be the maxim when considering the frequency of your carbohydrate intake.

References

Avner S, Robbins T. A Scoping Review of Glucose Spikes in People Without Diabetes: Comparing Insights from Grey Literature and Medical Research. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. 2025 Oct 25;18:11795514251381409. doi: 10.1177/11795514251381409. PMID: 41170150; PMCID: PMC12569367.

Costill DL, Saltin B. Factors limiting gastric emptying during rest and exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1974 Nov;37(5):679-83. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.5.679. PMID: 4436193. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/jappl.1974.37.5.679

Jones RO, Vaz DE Oliveria M, Palmer B, Maguire D, Butler G, Gothard I, Kavanagh K, Areta J, Pugh J, Louis J. Different Carbohydrate Ingestion Patterns Do Not Affect Physiological Responses, Whole-Body Substrate Oxidation or Gastrointestinal Comfort in Cycling. Eur J Sport Sci. 2025 Jul;25(7):e12336. doi: 10.1002/ejsc.12336. PMID: 40489306; PMCID: PMC12147858. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12147858/

Mears SA, Boxer B, Sheldon D, Wardley H, Tarnowski CA, James LJ, Hulston CJ. Sports Drink Intake Pattern Affects Exogenous Carbohydrate Oxidation during Running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020 Sep;52(9):1976-1982. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002334. PMID: 32168107. https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/fulltext/2020/09000/sports_drink_intake_pattern_affects_exogenous.15.aspx

Pfeiffer B, Stellingwerff T, Zaltas E, Jeukendrup AE. Oxidation of solid versus liquid CHO sources during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Nov;42(11):2030-7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0efc9. PMID: 20404762. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20404762/

Stocks B, Betts JA, McGawley K. Effects of carbohydrate dose and frequency on metabolism, gastrointestinal discomfort, and cross-country skiing performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016 Sep;26(9):1100-8. doi: 10.1111/sms.12544. Epub 2015 Aug 27. PMID: 26316418. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26316418/