Fat: the Ultra-Distance Fuel? Part Three - Chewing the Fat

If one were to seek out information relating to nutrition guidelines during exercise, whether via a search engine or through the research literature, the resulting output would almost solely revolve around carbohydrate intake.

The reason for this focus on replenishing carbohydrates during exercise is twofold. Firstly, as previously outlined, the body’s store of carbohydrates is limited. At all intensities, there will always be a contribution to energy production from carbohydrates and even oxidising fat requires the use of some carbohydrates. This is described as ‘fat burning in a carbohydrate flame’. In addition, carbohydrates are the preferred energy source of the brain and glycogen depletion is thus associated with acute cognitive decline.

But if we are exercising at an intensity where fat is the main fuel source, does this need to be replaced during exercise?

To answer this question, it will first help to understand how fat is metabolised to provide energy.

Fat Metabolism

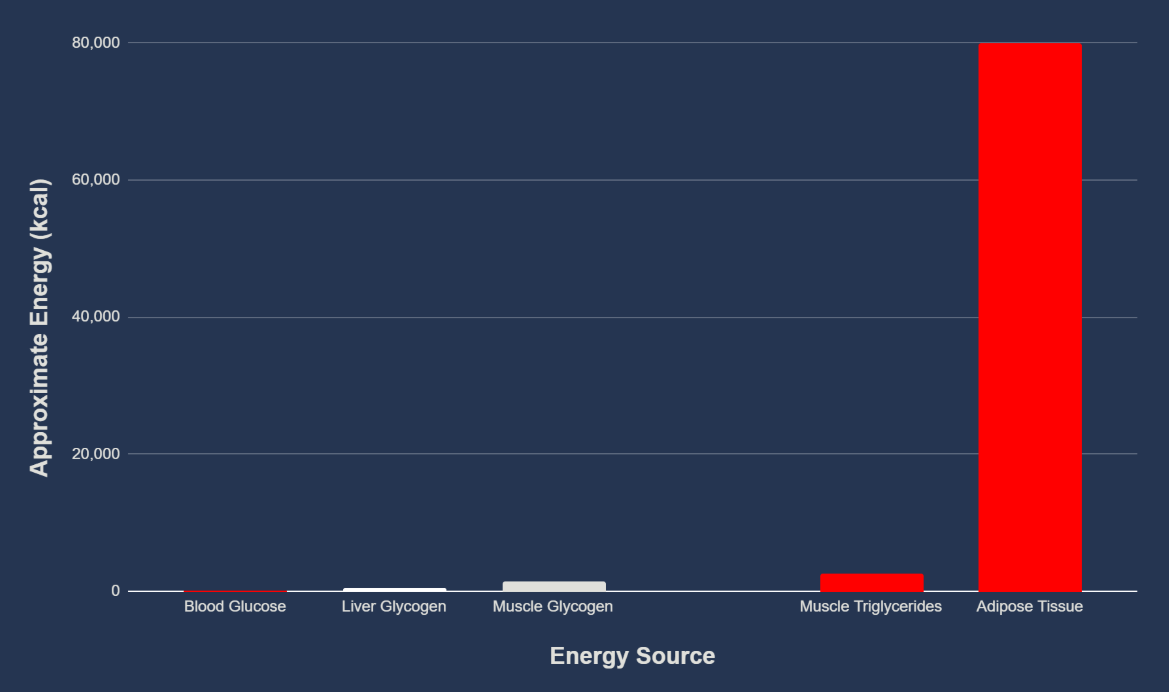

The principal form of fats ingested and stored in our bodies are triglycerides. Most of these are stored in adipose (fatty) tissue for future energy requirements. Fatty acids can then be released into the blood as Free Fatty Acids (FFA) where they travel to the muscles to be used for energy. Endogenous triglycerides (stored within the body) represent the largest energy reserve in the body, around 60 times greater than that stored as glycogen (Muscella et al., 2020). Immediately, it is clear that the body’s huge fat reserves are adequate to fuel multiple days of exercise, particularly at lower intensity levels, and therefore lower overall energy demands, where fat is the principal substrate used for energy production.

Comparison of the body’s energy sources (fat-derived sources on the right, carbohydrate-derived sources on the left). Adapted from https://us.humankinetics.com/blogs/excerpt/the-bodys-fuel-sources

Unlike carbohydrates, which when ingested enter the bloodstream and increase blood glucose levels rapidly (especially when high GI), there is a distinct process for ingested fat. It is also important to understand that converting fat into energy takes 2.4 times more oxygen than carbohydrates, illustrating why carbohydrates are the preferred fuel source at higher intensities.

There are two main forms of triglycerides found in foods. The most common are long-chain triglycerides (LCT), with the other being medium-chain triglycerides (MCT). Nutritional fats reach the circulation slowly, only entering the blood 3-4 hours after ingestion (Jeukendreup et al., 1998). Digestion in the gut and absorption of fat are also slow processes, with only a small portion of exogenous LCTs being oxidised within 6 hours of ingestion (Horowitz & Klein, 2000) as fats inhibit gastric emptying (the time it takes for food to empty the stomach). Eating fats consisting primarily of LCTs immediately before or during exercise is therefore not a direct source of energy used during subsequent exercise. Additionally, ingesting LCTs have not been shown to significantly alter substrate utilisation so you will not see improved fat oxidation or more glycogen sparing during any exercise that follows immediately.

MCT - The Fast Fat?

In contrast to LCTs, MCTs are more rapidly absorbed and thus potentially a more readily available source of energy. There are even sports nutrition products that contain MCTs for this reason. However, the amount of MCT that can be tolerated at one time is limited to 25-30g and ingesting more can cause adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. At this amount of overall intake the oxidisation rate is only 6-9g/hr, therefore providing a small amount of overall energy requirements, even at low intensities. As with LCT, ingesting MCT before exercise also does not increase total fat oxidation or spare muscle glycogen (Horowitz & Klein, 2000).

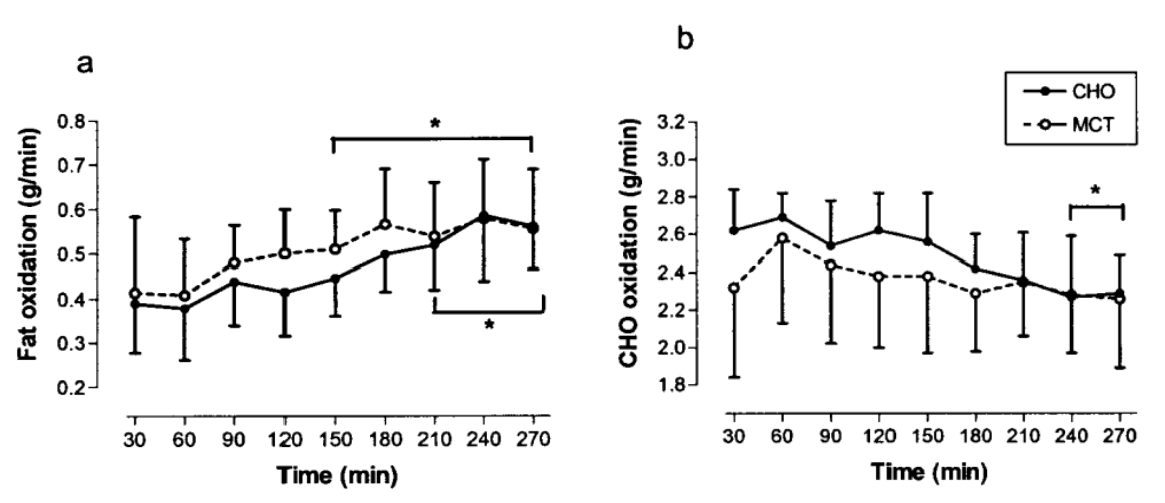

The effects of MCT and carbohydrate ingestion on ultra-endurance cycling performance was the subject of a study carried out by Goedecke et al. in 2005. Although their definition of ‘ultra-endurance’ at 270 minutes is very much on the ultra-short side, the outcome is instructive. Eight trained cyclists participated in this randomised, single-blind crossover study where on two separate occasions they cycled for 270 minutes at 50% of peak power output. One hour before the tests, the subjects ingested either 75g of carbohydrates or 32g of MCT and then ingested a carbohydrate solution or a carbohydrate/MCT solution respectively every 20 minutes during the test period. There was no difference in oxygen consumption or substrate utilisation between the groups and half of the MCT subjects experienced gastrointestinal symptoms. Ferreira et al. (2003) also carried out a review aiming to elucidate how MCT can influence performance in ultra-endurance exercises. They concluded that MCT supplementation for ultra-endurance exercises does not seem to promote a performance enhancement that would support its use due to insufficient evidence supporting that it spares the glycogen organic reserves or improves performance. On the whole, I would therefore side with Jeukendreup et al. (1998) who summarise that MCT does not appear to have the positive effects on performance that are often claimed.

Goedecke et al. (2005). Rates of total fat (a) and carbohydrate (b) oxidation during a 270 min exercise bout following ingestion of carbohydrate or MCT solutions.

Ultra-Specific Considerations

All the evidence therefore points to the simple conclusion that ingestion of fat during exercise bouts of any reasonable duration is not necessary, largely due to the body containing sufficient stores, the time taken to absorb and oxidise exogenous fats and the potential for gastrointestinal distress, or slowed gastric emptying, if overconsumed. You will likely be consuming fat incidentally when eating ‘real’ foods and this should pose no problem provided that it causes no gastrointestinal distress or inhibits your ability to also take on appropriate quantities of carbohydrates. However, we also need to consider when we are exercising for ‘unreasonable’ durations - i.e. multi-day ultra-distance events.

It is here where rethinking the intake of fat is necessary to account for practical issues such as satiety or food preferences, as well as plugging a potentially huge calorie deficit and replenishing endogenous fat stores. Indeed, Aktitiz et al. (2024) go as far to say that exogenous fat intake during an ultra-distance race can be critical for success, especially as the distance increases. Similarly, Nikolaidis et al. (2018) state that since ultra-endurance races are performed at a sub-maximal intensity, an increased intake of fat would not be detrimental for performance.

Beyond the first day of an ultra-distance event, you are likely to be relying more on solid food for fuel. As the intensity of the exercise is lower, carbohydrate requirements will not be as high and deriving a greater proportion of energy from fats can be more practical, both from gastrointestinal and palatability perspectives. Problems such as decreased taste sensation, discomfort from the sweetness of sports-specific products, loss of appetite and difficulty accessing food also need to be considered for multi-day nutrition strategies. Metabolic flexibility is therefore crucial, which comes from being familiar with consuming a variety of foods. Therefore, even if fats consumed in single-day training sessions may have no immediate benefit for that ride, when performing lower intensity extensive aerobic exercise there can be a ‘training the gut’ element to becoming familiar with a range of food sources.

To support this, the International Society of Sports Nutrition put out a Position Stand relating to nutritional considerations for single-stage ultra-marathon training and racing, where they analysed numerous studies considering energy intake in ultra-distance races (Tiller et al., 2019). Collectively, their data suggests that successful completion of ultra-marathons likely requires a higher degree of tolerance to both carbohydrate and fat intake (either as solids or fluids). Foods with a greater fat content were seen as advantageous during racing in terms of caloric provision per unit of weight and minimising pack weight when self-sufficient. Additionally, higher fat foods often contain more sodium, which may help mitigate the risk of exercise-associated hyponatraemia.

Balancing the Scales

It is also worth considering whether fats consumed during exercise may be required to replenish endogenous fat stores when distances and durations become very ‘unreasonable’. Jeukendreup et al. (2018) highlight that, although LCTs are not believed to be a major fuel source during exercise, they may serve to replenish triglyceride stores after exercise.

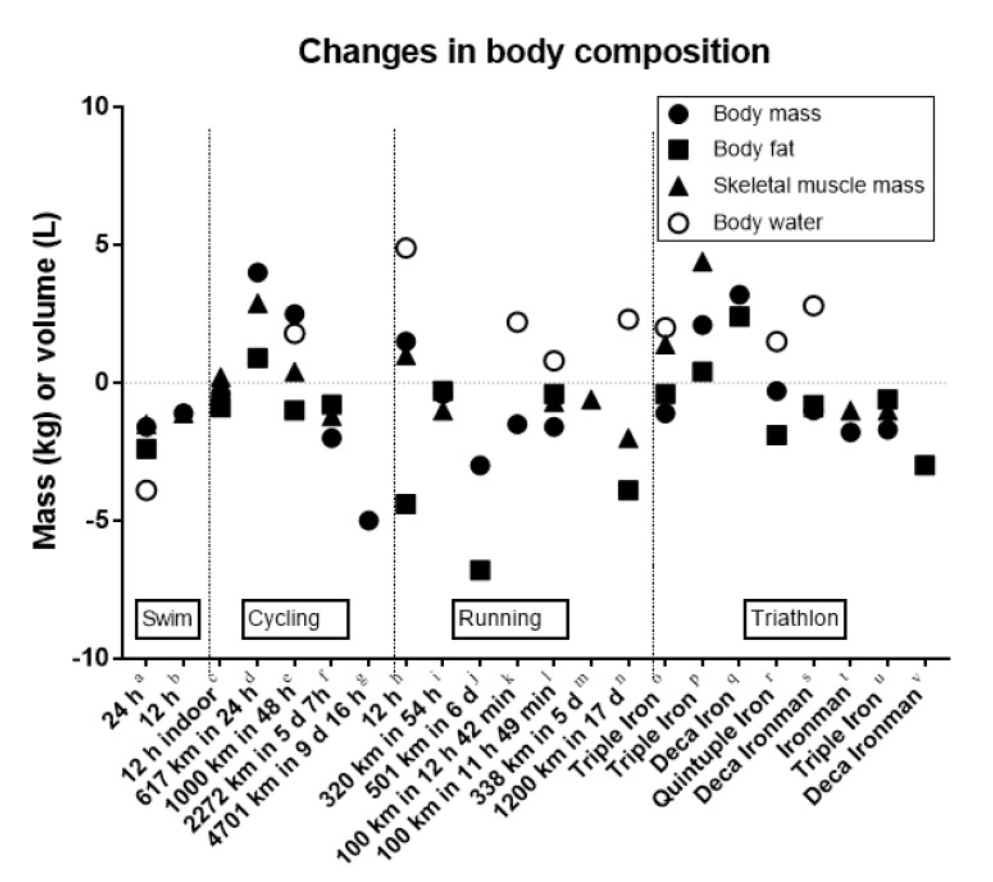

Nikolaidis et al. in their 2018 review of nutrition in ultra-endurance analysed changes in body mass percentage for a range of sports lasting various (ultra) durations. They found that body mass losses following an ultra-endurance race can reach levels greater than 5% of their starting body weight. Whether the loss of body mass reflects fat mass, skeletal muscle mass or a combination depended on the duration of the race. They also considered that it might be assumed that a concentric exercise such as cycling rather induces a loss of fat mass. However, the losses were not particularly drastic as on average the athletes lost ~0.5 kg in body mass and ~1.4 kg in fat mass across all of the sports and durations.

Nikolaidis et al. (2018). Change in body composition in ultra-endurance athletes competing in swimming, cycling, running, and triathlon.

There are suggestions that a loss in body mass and body fat can be offset through a high consumption of fat. Knechtle & Bircher (2005) studied an ultra-marathoner competing in a 6 day race who consumed 34.6% of his daily food intake as fat. Although body fat was lowered in the first two days of the race, it remained unchanged thereafter. This is indeed a high proportion of dietary fat as Nikolaidis et al. (2018) found that ultra-endurance athletes consume on average ~19% of ingested energy from fat, with athletes participating in longer races showing a higher intake of fat.

Given that ultra-distance athletes are consistently reporting significant energy deficits whilst primarily relying on carbohydrates for fuel and there being observations that energy intake correlates significantly with performance (see Black et al., 2012), an increase in fat consumption could therefore potentially go towards plugging this deficit. This should however not be to the detriment of adequate carbohydrate intake and is only likely to be truly beneficial when events span to multiple days and are performed at low intensities where fat is the predominant substrate utilised. Additionally, since a single gram of fat comprises 9 kcal as opposed to 4 kcal for carbohydrates, fats do provide more bang for their buck in this respect.

Fat as an Essential Dietary Component

Aside from specific performance considerations, dietary fats form a crucial component in overall health. It is here though that quality matters as much as quantity. Unsaturated fats offer greater health benefits and particularly the essential fatty acids (EFA) omega-3 and omega-6 which cannot be synthesised by the body so must come from our diet. EFAs are required for normal cell, tissue, gland and organ function, and may play a role in post-exercise recovery.

In their narrative review on nutritional strategies to improve ost-exercise recovery and subsequent exercise performance, Naderi et al. (2025) consider that there is a lack of evidence to support targeted replenishment of intra-muscular triglyceride stores to improve subsequent exercise performance lasting less than 3 hours, but caveat that future research in the context of repeated daily ultra-endurance performance is warranted. The EFAs omega-3 and omega-6, have also been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties and a capacity for reducing exercise induced muscle damage. Omega-3 fatty acids can enhance muscle protein synthesis, helping to repair muscle fibers post-exercise. Although consuming dietary fat can prolong gastric emptying times, as long as carbohydrate ingestion is adequate, glycogen resynthesis is not influenced by the addition of fat in the post-exercise period. Therefore including high-quality fat in the post-exercise window can be a reasonable strategy for maintaining vital functions and potentially aiding recovery.

Takeaways

Considering the evidence, there appears to be no immediate benefit to eating fats during training in terms of energy provision. The focus during these sessions should be on maintaining an adequate and appropriate carbohydrate intake. Fat intake at a reasonable level is unlikely to be detrimental, but acute consumption will not affect substrate utilisation during the current session. Only if there is a specific element of preparing for a multi-day ultra-distance event is there real interest in fat consumption during exercise, largely for the benefit of ‘training the gut’ and promoting metabolic flexibility. I wouldn’t advise filling your bidons with olive oil or eating peanut butter by the spoonful on every ride but treating this within the context of each situation. This should mean that when you are facing a calorific deficit during an event, your stomach will be better prepared to cope with whatever you choose to subject it to without experiencing gastrointestinal distress.

This could also potentially help to address this energy deficit and offset body mass losses, as well as drop-offs in performance. As is a common theme throughout the training process, balance appears to be where the evidence is pointing towards. The International Society of Sports Nutrition advises that the successful completion of ultra-distance events requires a degree of tolerance to both carbohydrate and fat intake. On balance, this sums up the matter well.

References

Aktitiz, Selin & Kuru, Dilara & Ergün, Zeynep & Turnagöl, Hüseyin. (2024). Nutritional strategies for single and multi-stage ultra-marathon training and racing: from theory to practice. Turkish Journal of Sports Medicine. 59. 70-87. 10.47447/tjsm.0807. https://journalofsportsmedicine.org/full-text/729/eng

Black, K. E., Skidmore, P. M., & Brown, R. C. (2012). Energy Intakes of Ultraendurance Cyclists During Competition, an Observational Study. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 22(1), 19-23.

Ferreira, Antonio & Barbosa, Paula & Ceddia, Rolando. (2003). The influence of medium-chain triglycerides supplementation in ultra-endurance exercise performance. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. 9. 413-419.

Goedecke, J. H., Clark, V. R., Noakes, T. D., & Lambert, E. V. (2005). The Effects of Medium-Chain Triacylglycerol and Carbohydrate Ingestion on Ultra-Endurance Exercise Performance. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 15(1), 15-27. Retrieved Dec 18, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.15.1.15

Jeukendrup AE, Saris WH, Wagenmakers AJ. Fat metabolism during exercise: a review--part III: effects of nutritional interventions. Int J Sports Med. 1998 Aug;19(6):371-9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971932. PMID: 9774203.

Knechtle B, Bircher S. Veränderung der Körperzusammensetzung bei einem Ultralauf [Changes in body composition during an extreme endurance run]. Praxis (Bern 1994). 2005 Mar 9;94(10):371-7. German. doi: 10.1024/0369-8394.94.10.371. PMID: 15794360.

Jeffrey F Horowitz, Samuel Klein, Lipid metabolism during endurance exercise, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 72, Issue 2, 2000, Pages 558S-563S, ISSN 0002-9165, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/72.2.558S.

Muscella A, Stefàno E, Lunetti P, Capobianco L, Marsigliante S. The Regulation of Fat Metabolism During Aerobic Exercise. Biomolecules. 2020 Dec 21;10(12):1699. doi: 10.3390/biom10121699. PMID: 33371437; PMCID: PMC7767423. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7767423/

Nikolaidis PT, Veniamakis E, Rosemann T, Knechtle B. Nutrition in Ultra-Endurance: State of the Art. Nutrients. 2018 Dec 16;10(12):1995. doi: 10.3390/nu10121995. PMID: 30558350; PMCID: PMC6315825.